by Alex Berenson, Unreported Truths:

Even before the Hamas attacks on Oct. 7, I probably spent too much time thinking about John Wells.

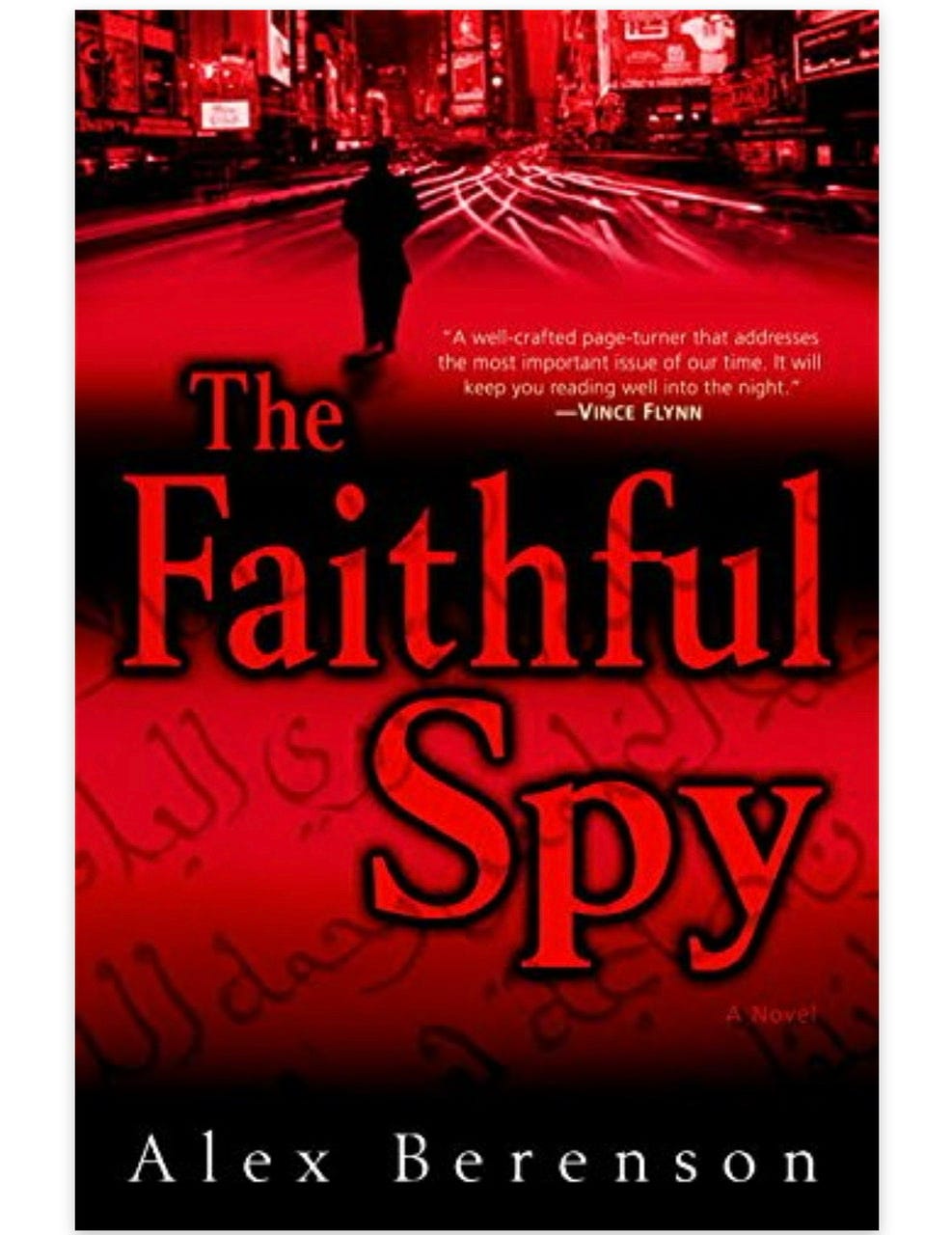

If you know me mostly from Unreported Truths, you may not be aware I spent a decade writing spy novels. Ironically or not, my only real writing award is for fiction. In 2007, my debut, The Faithful Spy, won the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for Best First Novel. It beat out Sharp Objects from Gillian Flynn, who later sold a few million copies of Gone Girl.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

Wells, an American convert to Islam, is the hero of The Faithful Spy, and my next 11 novels, up to The Deceivers, in 2018. Though hero is an interesting word to use, since The Faithful Spy opens as The Deceivers ends, with Wells killing men who pose him no direct threat. In other words, he is an executioner from beginning to end.

—

(Buy it, you’ll see.)

—

The Wells novels are called spy novels, but Wells is a soldier as much as a spy. He’s not out of John le Carre. He’s not at home at headquarters. He’s not James Bond, either. He’s not fancy. He and his enemies don’t make long speeches. They rarely even make threats. They don’t need to. When they fight, it’s usually to the death, it’s usually with guns, and it usually doesn’t take long. In other words, the violence in the Wells novels is real, not cinematic.

The only cinematic aspect is that Wells always lives. Or survives, maybe survives is a better word.

When I first thought of Wells, I thought of him as a classic Western character. Think Shane, or High Noon. The fact he’s from Hamilton, Montana, up against the Bitterroot Mountains, is no accident. But he came to life from the soldiers and Marines I saw in Iraq when I was a reporter for the Times in 2003 and 2004.

Back in the day, I heard from a fair number of soldiers about Wells. They liked him. They felt he captured something authentic in their experience, notwithstanding my occasional cringe-inducing technical errors about weapons (no matter how hard I tried, I seemed unable to avoid one per book).

Wells has what the best soldiers do, absolute calm under pressure. This is something deeper than mere physical courage, an almost relaxed acceptance that death is inevitable, that it can be dodged but never beaten, and so it is to be accepted rather than feared.

And the flip side, too, an absolute willingness to kill in battle with no more regret (or joy) than a lion kills a gazelle – an animal knowing only that its choice is to kill or starve.

But those two gifts are nothing, worse than nothing, when they are not paired with the moral courage to use violence only when it is necessary. The difference between psychopath and soldier does not lie in the body count.

—

And the last four years should have taught us all that courage comes in many different flavors, and they aren’t fungible.

What I mean: the courage to die for a cause is very different than the willingness to judge that cause. Both of those are not the same as the willingness to stand up to poor or misguided leadership. Someone can be very physically brave without having intellectual or moral courage.

A few days ago, the Israeli government showed the world evidence the atrocities that Hamas committed on Oct. 7. Among the videos of executions and photos of mangled corpses was a recording of a Hamas terrorist calling his parents to brag that he had killed 10 Jews.

And a cartoon appeared on Twitter purporting to show the difference between the two sides:

—

But of course that’s not the real difference.

That’s not the choice Israel faces.

Both sides are killing, and the Israeli army and air force have already killed a lot more Palestinians than Hamas has killed Israelis.

The choice is whether to kill for the sake of killing or for the sake of saving.

A few months ago, I read The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larsen’s history of the Blitz – the year of German air attacks on London and the United Kingdom. Larsen captures the horror of the attacks, which came night after night and killed about 40,000 English civilians before sputtering out as Germany turned its attention to the Soviet campaign.

Read More @ alexberenson.substack.com